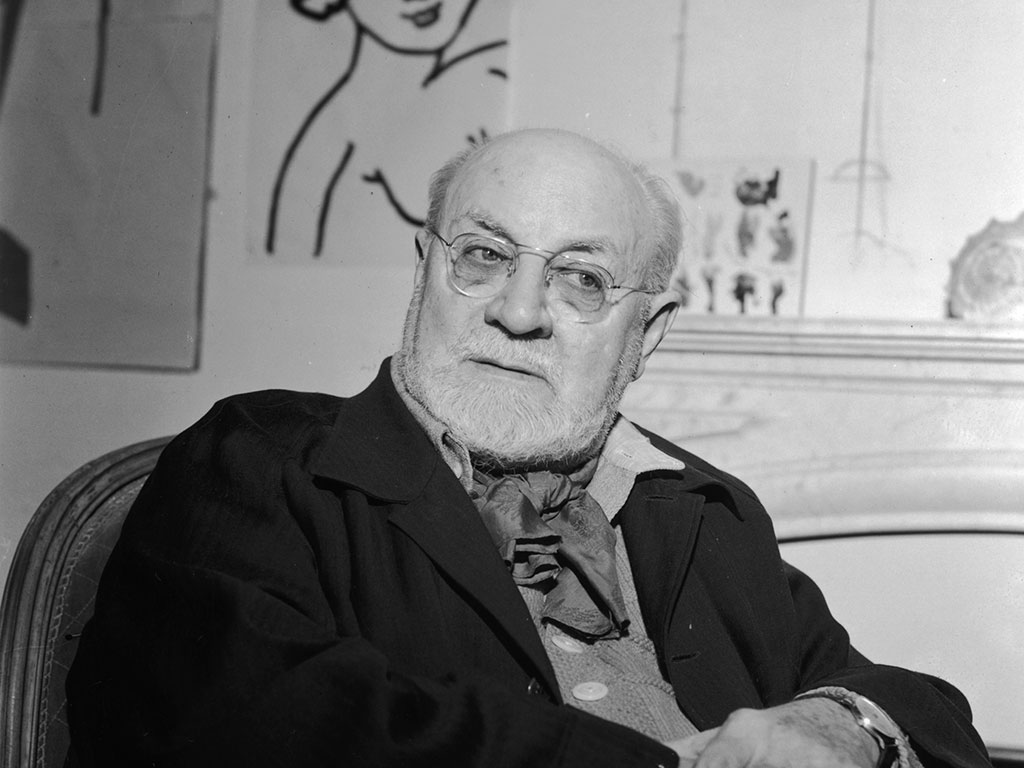

One of modern art’s leading figures, there are few artists more important than Henri Matisse. Born on New Year’s Eve 1869 in Le Cateau-Cambrésis in the north of France, Matisse’s career would be long and prolific. He started painting in 1889 after an attack of appendicitis forced him into a period of convalescence and his relationship with the craft would only end when he was physically unable to continue.

In his late 60s a period of poor health forced Matisse to stop painting. He started making paper cut-outs with scissors to draft commissions. Eventually he would decide that he preferred the new medium, and it led to some of his most famous pieces.

A comprehensive collection of the cut-outs or gouaches découpés, is making its way around the globe, visiting prominent galleries including MoMA, presenting a rare opportunity to see these later works in one place. Its latest stop is as part of the Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs exhibition at the Tate Modern in London, where some of his work had already been housed.

Against all odds

To understand the importance of Matisse’s cut-outs, it is necessary to examine the tragedy that led to them. A bitter separation from his wife led to an empty studio just before the outbreak of the Second World War, as lawyers prepared to fight over his assets. Then, in 1941, he was diagnosed with cancer. For a long time he struggled with the idea of death, writing letters to his family before undergoing surgery in Lyon.

The cut-outs represent more than an important work of modern art; they represent a man’s struggle and his success against the odds

At the time, the doctors gave him three years to live, at most. “I love my family, truly, dearly and profoundly,” he said in one letter to his son Pierre, fearing that the worst might happen. He reconciled with his wife, and for the next two years he battled against illness and surviving the war. By 1943 he was bedridden, almost invalid, amid a war that showed no signs of abating.

Even worse, Matisse feared his creativity would not survive the procedure unscathed. The reality could not be further from the truth. Although he was forced to use a wheelchair, he called the period after this operation his seconde vie – second life.

With a second life came a burst of originality. Matisse called the cut-outs “painting with scissors”. The artist felt his best works came after his period of illness. He said: “Only what I created after the illness constitutes my real self: free, liberated.”

Despite his limited movement and failing strength, he effortlessly created works with renewed vigour and imagination. He worked from either his bed or a wheelchair, never fully physically recovering from the illness and operation, but his mental strength remained. In some ways, it seems a confrontation with mortality benefitted Matisse, as he was able to strip his work down to the bare minimum.

Matisse always insisted that the cut-outs were, at heart, no different from his work before his illness. “There is no gap between my earlier pictures and my cut-outs,” he wrote. “I have only reached a form reduced to the essential through greater absoluteness and greater abstraction.”

In his book Jazz, Matisse explored the medium through thoughtful pictures – almost 100 in total – taking inspiration from music and theatre.

Labour of love

Matisse soon developed an efficient method for producing the cut-outs. Often the artist would sit surrounded by coloured card cut into precise shapes. For hours at a time he would cut out, assemble, re-assemble and cut again to form a bigger picture. He called his studio a factory, as he produced work after work in rapid succession.

Speaking of the process in Amis de l’art in 1951 Matisse said that the cut-outs allowed him “to draw in the colour”. He said: “It is a simplification for me. Instead of drawing the outline and putting the colour inside it – the one modifying the other – I draw straight into the colour.”

All of the results are striking, enduring and emotive. The first of his cut-outs is perhaps the most important, a piece called The Fall of Icarus. It clearly represents Matisse’s fear that his artistic days were over. Marking the beginning of his complete transition to cut-outs, the piece inspired many artists to follow in the Frenchman’s footsteps, including the hard-edge style of composition, where colours are chosen to form abrupt transitions as opposed to smooth blends.

Early cut-outs were small, but as Matisse’s courage and confidence in the medium grew, the compositions grew in size and complexity. Later works are big, colourful and striking. There is a popular rumour that they were so large and vibrant that his doctor insisted he wear dark glasses when he worked, to avoid eye damage or headaches.

Matisse’s iconic Blue Nudes, depicting a female figure cut from blue in intricate shapes on a white background, are an excellent example of his final body of work. The abstracted figure’s distinctive pose has made this piece one of his most recognisable. He particularly enjoyed posing the figures in his signature style – one arm raised, legs entwined. Stephen Farthing writes that the colour blue had deep significance to Matisse, representing depth and distance.

![Henri Matisse (French, 1869-1954). Two Masks (The Tomato) (Deux Masques [La Tomate]), 1947. Gouache on paper, cut and pasted. 18¾ x 20 3/8 (47.7 x 51.8 cm). Mr. and Mrs. Donald B. Marron, New York. © 2014 Succession H. Matisse, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York](http://www.businessdestinations.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Two-Masks-The-Tomato.jpg)

The work is an excellent example of late-fauvism, a style that Matisse contributed to in the early twentieth century. Fauvism utilises strong colours and ran at odds to impressionism, preferring to preserve painterly qualities over realistic ones. Interestingly, the cut-out Blue Nudes share their name with a work from earlier in his career – one that many consider repulsive because of its lack of obvious aesthetic or beautifying qualities. Indeed, the figure in the 1907 version is nigh androgynous, and many experts regard the later Blue Nudes as a further abstraction to remove all but form and colour.

Lasting legacy

Matisse’s most famous cut-out remains The Snail. Housed at the Tate since 1962, the piece was created at a distance, with a white piece of paper attached to a hotel in Nice. He would cut the shapes and hand them to an aide, who would pin them to his exact specifications. When he was finally happy, the shapes were stuck down, creating the now-distinctive spiral pattern. Speaking to André Verdet, Matisse said: “I first of all drew the snail from nature, holding it. I became aware of an unrolling, I found an image in my mind purified of the shell, then I took the scissors.”

Matisse continued creating work well into his 80s, and when he passed away in 1954, aged 84, he had already cemented himself as a giant of modern art. He is interred in the cemetery of the Monastère Notre Dame de Cimiez near Nice, with his wife. His works continue to draw universal acclaim and interest – recent high-profile sales of some of his pieces prove this – but the popularity of the worldwide tour of his work proves the importance of Matisse to modern art.

To his admirers, Matisse was a visionary. The cut-outs represent more than an important work of modern art; they represent a man’s struggle and his success against the odds. The final chapter in the artist’s life, they are a monument to his mastery of colour and composition, and, above all, his rare talent.