If the first firework wasn’t enough, the second deafening crack certainly raised mine and the crowd’s collective awareness. Then the madness started.

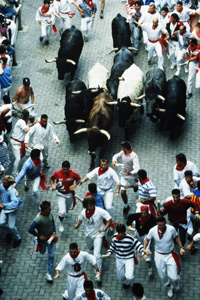

The first runners could be seen in the distance in the canyon-like confined street of Santo Domingo. Their progress was so sluggish they appeared to be running in treacle; their expressions tightened as the bulls bore upon the stragglers.

The bulls run at a blistering pace – covering 100m in around six seconds. That’s nearly twice as fast as an Olympic sprinter. Within seconds of the first firework foolhardy souls are swamped. From the safety of the sidelines you could see bodies crush in slow motion as the six bulls piled into them sliding and skittering on the shiny cobbles like a deer on ice.

For most of the year, Pamplona, located in the north-eastern province of Navarra, is just like any other Spanish provincial town. In July though it is transformed into the focus of an international bacchanal – the annual nine-day festival of San Fermin – the patron saint of Navarra.

The most famous part of the cermony is the Running of the Bulls, or Enceirro. This breathtaking display of bravery first attracted Ernest Hemingway, and brought this spectacular and deadly custom to a wider audience. Originally, men from the surrounding arid landscape would have taken part. The documented history of the enceirro dates back to the 16th Century, though its roots extend back through the mists of time to the era when Spain first embraced Christianity. Now Pamplona’s population of nearly 200,000 swells ten fold during the San Fermin celebrations to welcome 2 million visitors. With epic parties and guaranteed action, it should come as no surprise that this is one of the must-see events on the international backpacker circuit. Today, thousands of runners, wannabe runners, thrill seekers and party goers make their way to this small town each July for the eight day fiesta. Hotel rooms are like gold dust, booked months in advance, the festival running all day everyday for eight days. And despite the late nights, the Enceirro takes place every morning at 8am sharp. This distilled Spanish spirit has to be witnessed first hand.

Unlike bull-fights, which are performed by professionals and idolised as gods, anyone feeling brave enough may take part in an encierro. However, most of the men who participate are young and athletic – but they’re not athletes. Athletes train morning noon and night for a race; the only training these chaps have done for the last week or so are short repetitious curls of their drinking arms.

A heavy and constant intake of alcohol in the approaching to the running of the bulls is almost as traditional as the event itself. And who can blame them, with the bulls weighing as much as 1,500kg, you need all the confidence beer can muster. Injuries are common; both to the participants who may be gored or trampled, and to the bulls, whose hooves grip poorly on the paved or cobbled street surfaces.

Since 1924, 13 people have been killed. The last was a 22-year-old American, Matthew Peter Tassio, who was gored in 1995. This year’s festival is due to pay a special tribute to him to mark the 10th anniversary of his death. Another famed runner, Fermin Etxeberria Irañeta, died in 2003. Etxeberria, 63 when he died, had never suffered an injury in 350 runs. Anyone who survives a close encounter with a panicky bull is said to have been protected by San Fermin’s cloak.

At about 7am, stewards and officials begin to barricade off the streets; the course the bulls run takes shape. Using large pieces of wood fencing, the officials mark well worn route through the cobblestone streets. The rudimentary fence is about six feet high and is made of two sturdy cross bars of thick rough-sawn wood – one for stepping on to get over the top and the other as the top.

The fence also had large gaps on the bottom for people to slide under if they are being chased by the bulls and want to make a quick escape. Of course, during the melee, there are thousands of spectators crushed up against the fence, so finding solace behind it isn’t that easy.

Around 7:30am, workmen began to hose down the streets in readiness for the main event. The half-mile (848-metre) route – extends from the inclined street of Santo Domingo to the city’s bullring. The chase rarely lasts more than three minutes, unless one of the bulls becomes separated from the herd.

Stray bulls become extremely agitated, and so the organisers arrange for a second release of calmer and older steers to run through the streets in order to pick up any straggling bulls. The first firework announces the release of the bulls from their corral, and a second signals that the last bull has left the corral.

From there, the animals stamped along Santo Domingo and cross the Town Hall Square. As the chaos intensifies, the charge enteres Calle Mercaderes – this street signifies the beginning of the most treacherous stretch of the course. A dangerous blind curve leads into the Calle Estafeta, the longest and most infamous part of the route.

Although all the stretches are dangerous, the curve of the Calle Mercaderes and the stretch between the Calle Estafeta and the Bull Ring are those which hold the most risk. This is where the casualties rise. Immediately after is the Calle Duque de Ahumada – known locally as as the Telefónica. This gives way to the dead end street which leads to the bull ring. Thankfully, nobody was badly injured on this occasion, but with enceirros taking place for the following week, gorings are common.

As the mayhem approached my vantage point, the crowd of white-clad runners suddenly split to reveal a snorting bovine mass. Only now did I understand the threat to the runners faced from its sharp horns and rippling black body was entirely real.

“If you go down, stay down,” was the advice I heard offered by one San Fermin veteran.

As the chaos passed, the mayhem abated almost as quickly as it came. The chase entered the bull ring enclosure and a third rocket arced into the sky. Inside the crowd enjoyed the spectacle of the runners being tossed in the corrida, and other tender parts. The fourth firework indicated that the beasts were safely sequestered in the bullpens and the Bull Run was over.

Of course the danger and mayhem doesn’t stop the thousands of men who’ve come here to prove their worth in the face of galloping adversity. To the outsider it might seem like a spectacularly futile exercise, but that would be missing the point. The enceirro is a blinding metaphor that encapsulates the indomitable spirit of Spain.